Every spring, Quirks & Quarks features our ever-popular listener question show, where we find experts to answer your questions.

But there remain some big questions we can’t yet begin to answer.

Here are 10 mysteries that science has yet to unravel.

1. What is the universe made of?

The stars, planets, and galaxies we see in telescopes make up only about five per cent of the known universe. The rest of it is made of dark matter and dark energy. And when scientists use the term “dark” that really means: “We don’t know.”

Dark matter is thought to be an invisible substance that does not give off light but has mass enough to exert the gravitational pull that holds entire galaxies together. Without it, the stars in our Milky Way would fly off in all directions like water drops from a lawn sprinkler.

Dark energy appears to function to speed up the expansion of the universe, operating on large scales to counteract gravity. But beyond seeing its effects, we have little understanding of what it could be.

2. Are we alone in the universe?

Our galaxy contains hundreds of billions of stars, and there are hundreds of billions of galaxies out there. Astronomers find that most stars seem to have several planets going around them which makes for at least trillions of other worlds. Yet despite these enormous numbers, we have yet to find a single sign of alien life. It could be hiding underground on Mars, beneath the ice of moons orbiting the giant planets, or on Earth-like worlds orbiting other stars, but as yet there is no hard evidence to show that any life exists other than on Earth.

That doesn’t mean ours is the only planet with life in the universe; we simply haven’t found it yet. But that doesn’t stop us from wondering whether it will take the same form as us, and, if we do make contact, how we’d prevent biological cross-contamination and how we would communicate.

3. How did life on Earth begin?

We think that, somehow, billions of years ago, chemicals came together to become self-replicating, evolved into simple cells, then organized into groups of cells, differentiated into tissues in complex organisms, and then one tiny side branch of the rich tapestry that resulted developed brains to contemplate it all.

The transition from chemistry to biology was attempted as a laboratory experiment in 1953 by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey, where the gasses methane, hydrogen and ammonia — along with water — were placed in a sealed flask and exposed to electric shocks for a week. The result was the formation of a dark substance on the inside of the flask that included amino acids, the building blocks of life.

But even though the Miller-Urey experiment is now done routinely, so far, no life form has crawled out of the flask. Maybe the lab experiment needs to run for a billion years or so to figure out how the Earth did it.

4. What is consciousness?

As you read this, millions of neurons are firing in your brain, perceiving these dark markings on your screen and forming them into words, sentences and thoughts. Exactly how the electro-chemical reactions taking place inside your skull give you a sense of identity, recreate memories of your past life, trigger curiosity, laughter, love, anger, and fire your imagination is a complete mystery. There are several theories and many ongoing debates just trying to define consciousness in the first place, let alone how it works and how it shapes human existence.

Nor do we know how far this sense of self extends in the tree of life. What do other animals with brains think about?

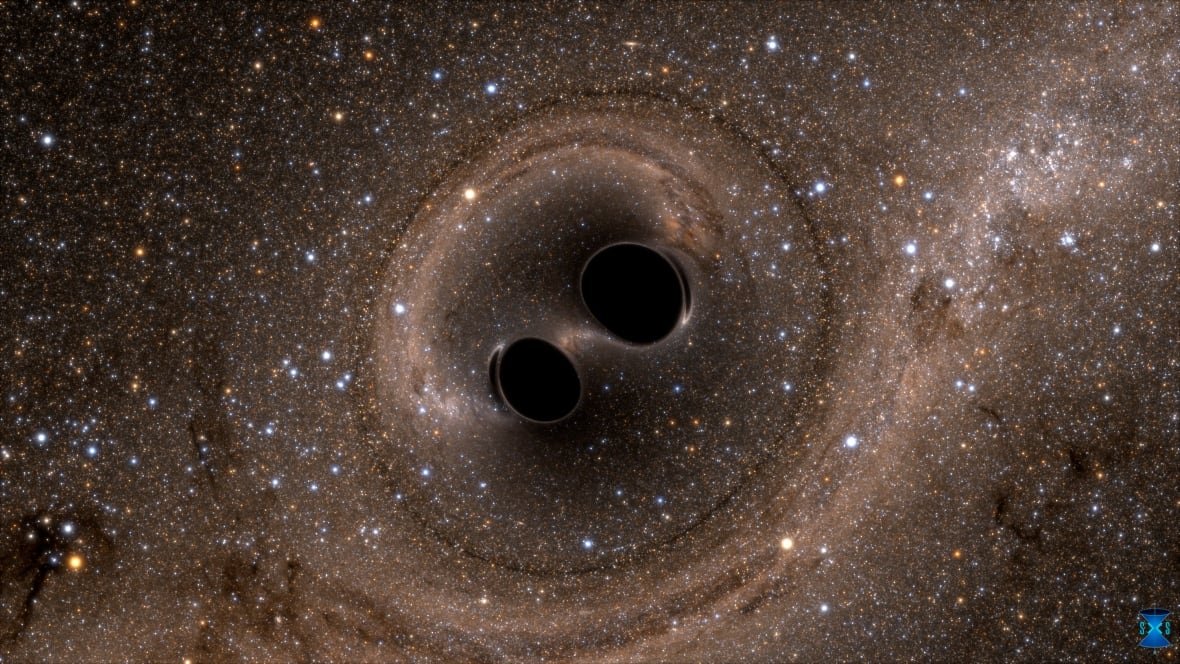

5. What is inside a black hole?

We know black holes exist and we even have images of material falling into them at the centres of galaxies. But what ultimately happens to that material is unknown because no one has been through a black hole to find out. Even if they had, we wouldn’t know about it because information only flows into a black hole, not out.

At the heart of the black hole — also known as the singularity — the laws of physics break down. The gravitational pull from the hole is so strong, an object falling in reaches the speed of light and eventually collapses down to a point. Those conditions are impossible to recreate on Earth.

Some suggest that a black hole is a gateway to a parallel universe, or that our whole universe itself could be inside a black hole.

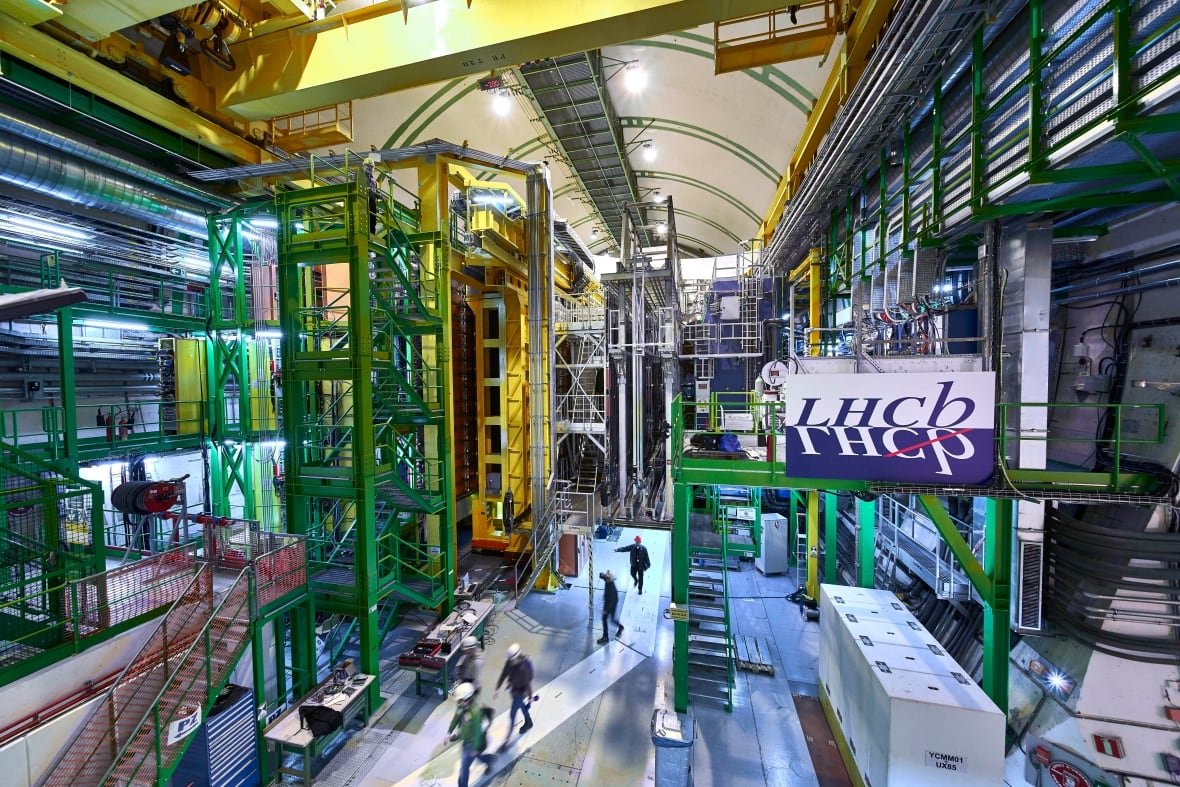

6. What went bang, and was there anything before?

The universe is expanding, growing outwards in all directions every second. If you run time backwards, everything must have been squeezed into something infinitely dense and hot. As with a black hole, it was a singularity — a condition physics can say nothing about.

What was it, and why did it suddenly expand explosively 13.8 billion years ago? Did it come from an earlier epoch when material came together in a big crunch, then rebounded outwards? Or did something come from nothing? In quantum physics, that can happen.

The Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, is trying to recreate the conditions at the moments after the Big Bang on a microscopic scale for a few billionths of a second to find what it can reveal about what went bang.

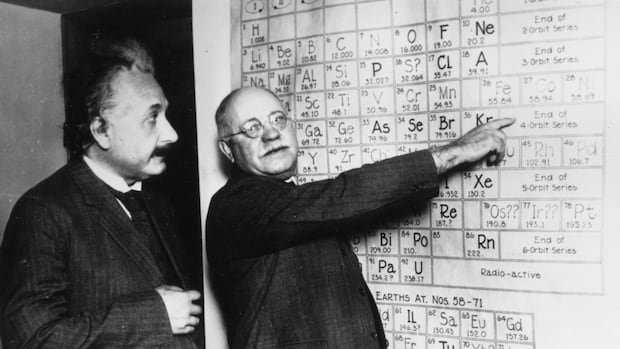

7. Is there a theory of everything?

Einstein’s theories of gravity and general relativity appear to work on the largest scale of the universe. They adequately describe what holds you in your chair and keeps galaxies rotating.

Quantum theory works on the scale of the very small, accounting for the behaviour of electrons, protons, neutrons, quarks, neutrons and other subatomic particles. But there is no unifying theory that brings these two realms together.

There have been attempts to construct such theories — string theory and loop quantum gravity are two examples. But these attempts have not yet been successful. When a complete theory of everything is developed, it will connect all the forces of the universe, and, presumably, help us understand some of the other questions on this list, such as the origin of the Big Bang and the inner workings of black holes.

8. Is time travel possible?

Yes. You’re doing it right now. But only in one direction, and largely at the same rate as everyone else on Earth. It is possible to time travel into the future. According to the theory of relativity, the faster you travel, the slower time passes for you compared to someone standing still. If you returned from a spaceflight that took you close to the speed of light, you would find yourself in the future on Earth, possibly with all of your friends long gone. In other words, time is flexible. Of course our current spaceships cannot come anywhere near the speed of light.

Time travel in the other direction is a different matter. We have no physics that allow us to understand if that is possible. And apart from that, if it were possible, we might have a problem locating the past. Time travel would also have to include space travel because you would need to go back to where the Earth was at that time. Considering the Earth moves around the sun at about 30 kilometres every second, and around our galaxy at 237 kilometres every second, that’s a long trip.

Perhaps that’s where all the tourists from the future are located. They are lost in space looking for the Earth.

9. How do we provide for a growing human population?

There are now thought to be more than eight billion people on Earth. That’s up from one billion in 1800 and six billion in 2000. While in much of the world the population growth rate has decreased in recent years due to families having fewer children, our numbers are still expected to reach 10 billion by 2060.

The challenge is to find ways to grow enough food, provide clean water and energy to supply such a large population without exhausting the Earth’s resources and undermining the ecosystem that sustains us. The solution is some combination of sustainable technologies and behavioural change.

This is more than a problem for science to solve. It is also a political, social and cultural issue.

10. How will the universe end?

It will take many, many billions of years, and we don’t know for sure, but these are the options that scientists discuss:

If the universe continues to expand forever, eventually everything will drift so far apart the distant galaxies will fade beyond our horizon. Eventually all the stars in our galaxy will go out and the universe will slowly cool into the big freeze.

That’s if dark energy doesn’t continue to become more powerful, and everything, including the very fabric of space time is torn apart, in what is called the big rip.

On the other hand, if universal expansion stops, gravity could pull the whole thing back together into the big crunch, collapsing the universe into a singularity that perhaps goes bang all over again.

Time will tell — though let’s hope this is one we never find out.