Summers have never been quite the same since June 20, 1975, and it’s all thanks to a “mindless eating machine” that terrorized moviegoers and beachgoers alike. That was the day Jaws hit theatres, ushering in the era of the summer blockbuster and becoming a pop culture phenomenon that still resonates 50 years later.Â

Steven Spielberg’s classic tale of a great white shark stalking the waters off an island beach town in New York state and devouring unsuspecting swimmers, broke records and became the first film to cross the $100-million US mark at the box office.Â

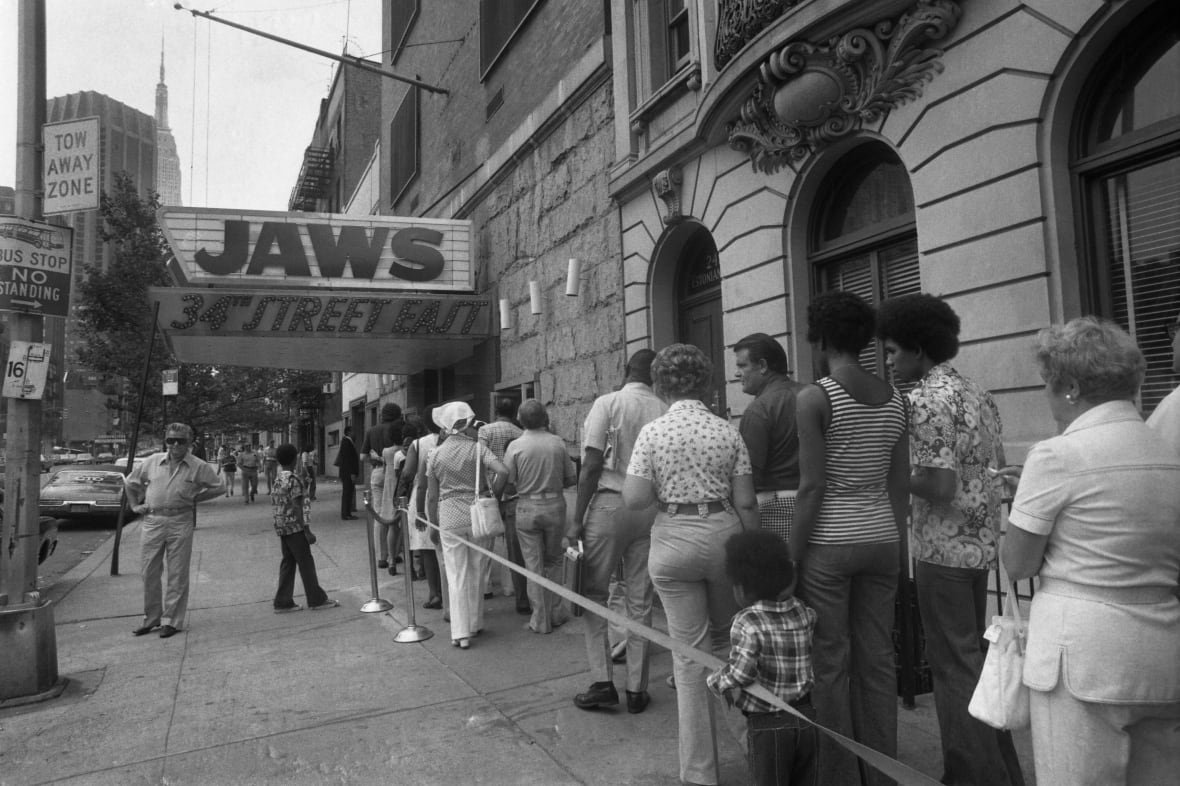

The film was credited with helping “revitalize” the movie landscape in what was a slumping year, The New York Times reported at the time, as people lined up outside cinemas for hours.

Since its release, we’ve come to expect a summer chock full of action-packed films that thrill and chill. What sets Jaws apart, even today, is how it influenced not just the movie industry, but the real world, too.

There’s a reason we’re still talking about Jaws, says Charles Acland, a communications studies professor at Montreal’s Concordia University and author of the book American Blockbuster: Movies, Technology, and Wonder.Â

“It is an expertly constructed motion picture,” he said, but it also got into our heads and made it “hard not to think about sharks for a few years and maybe even ever since.”

Jaws made us imagine our deepest fears

Chris Lowe was around 11 years old when the film came out. He grew up on Martha’s Vineyard, off the coast of Massachusetts where it was shot, swimming and fishing in those same Atlantic waters that became the fabled hunting ground for the ocean’s most notorious apex predator.

Jaws didn’t frighten him because he watched it being made, and a lot of familiar faces from his town made it into different scenes. But he certainly got a kick out of how scared others got.

Lowe also knows a thing or two about sharks: he’s the director of Shark Lab, at California State University Long Beach, and has been researching sharks for 30 years. He says the film actually influenced him and a lot of other shark biologists.

Did you know there are great white sharks in Canadian waters? If you said no, youâre not alone. Shark sightings in the Maritimes have risen and this team went on a mission to learn about these misunderstood predators. Watch Jawsome: Canada’s Great White Sharks on CBC Gem.

According to Lowe, very little was understood about great whites at that time â something Spielberg played to in the film.Â

“What made that movie work, believe it or not, was the fact that you rarely saw the shark and the storytelling allowed people’s imaginations to run wild,” Lowe said.Â

You don’t actually see the shark, a 7.6-metre animatronic beast nicknamed Bruce, until 81 minutes in â during that unforgettable, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat” scene (don’t worry, it’s embedded below). In total, it’s only on screen for about four minutes.

But Lowe says that was, and still is, enough to make people think twice about going into the water. He says people who’ve seen Jaws can almost hear the eerie “dun dun” of the iconic score by John Williams when they go for a swim, leaving them wondering what’s lurking beneath the surface.

For Lowe and his friends, the terror Jaws inspired wasn’t the worst thing in the world in the summer of 1975.

“Nobody else would go in the water that summer,” he said. “So, we had a lot of the beaches all to ourselves.”

We’re gonna need a bigger blockbuster

Jaws, based on Peter Benchley’s bestselling 1974 novel, came to define what we now think of as a blockbuster.

It raked in more than $260 million US worldwide during its initial release â a huge sum for that time, and still a lot. Adjusted for inflation, that works out to more than $1.5 billion US.

It was nominated for four Academy Awards, including best picture (it lost to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), best editing, best sound mixing and best original score (all of which it won).Â

For better or worse, it spawned a series of sequels and inspired an entire genre of shark attack films â from the suspenseful Open Water, to the gory but implausible Deep Blue Sea, to the downright absurd Sharknado franchise (Lowe is a big fan).Â

However, Acland says it’s a misconception that the movie was the first Hollywood blockbuster.

Before Jaws, he says, the word blockbuster was a promotional term used to describe epic films like Lawrence of Arabia and Ben Hur.

Then, with its ubiquitous marketing campaign and a remarkable 14-week run at the top of the box office, Jaws became an event for moviegoers young and old. Acland says the film “colonized summer,” which suddenly became a time for an “entertainment heavy movie.” In its wake, horror, sci-fi and action flicks came to dominate the season.

Taking the bite out of shark fears

Like blockbuster releases, sharks have become a fixture of summer culture thanks to Jaws, says Lowe.Â

The film has often been blamed for stoking fears about sharks and blowing the risk of attack out of proportion. Â

“I think Peter Benchley and Steven Spielberg both felt really bad about how it influenced people’s attitudes toward sharks,” Lowe said.

Fatal shark attacks are rare. The Florida Museum of Natural History’s International Shark Attack File confirmed 47 unprovoked shark bites on humans worldwide last year â only four were fatal. That’s one less than the number of people killed in Jaws.

By the time the movie came out, Lowe says, the great white shark population had already dwindled due to over fishing. He actually credits the film with bringing more attention to the species, ultimately leading to conservation and protection efforts that have seen populations grow since the 1990s.Â

Sightings, including off Atlantic Canada, have also increased, which Lowe says is helping people understand that sharks aren’t “as dangerous as they’ve been made out to be.”Â

Because of that, he says it might be difficult for a film to have the same impact today that Jaws did 50 years ago.Â

“I think that the science, the data that we have really flips Jaws on its head and show that whole ‘they’re out to get you’ thing is wrong.”